W1seGuy, hints to get you going

Welcome to W1seGuy, a room that’s as beginner-friendly as a puppy with a security badge! It’s advertised as easy and focused on decryption. Some programming skills are a must, but don’t worry. No need to dust off your ancient spell books just yet.

I whipped up a Python script with just a few lines of code that snags the encryption key faster than you can say “bruteforce.” Speaking of which, I initially went down the bruteforcing rabbit hole myself before realizing that, yes, this room is indeed EASY! So, let’s dive in and decrypt like pros, shall we?

Introduction to XOR encryption

First things first, I could just hand you the script and let you grab those flags like free samples at a supermarket. But where’s the fun in that? More importantly, you wouldn’t learn a thing. I’m here to challenge you to push further on your own by sharing my journey through this room. I started as a full n00b in decryption and learned a ton about the XOR encryption method along the way. I hope you’ll allow yourself to do the same by not scrolling all the way at the end right away.

The room starts with the source code, but we’ll get back to that later. Let’s first netcat into the machine and see what we’ve got:

┌─[user@parrot]─[~]

└──╼ $netcat 10.10.56.68 1337

This XOR encoded text has flag 1: 03297b303866005a253c1219420a3c235555202b160f4478293b2d4f231d25154f7b3d2519793935

What is the encryption key?

We get a very long integer. Let’s look at the beginning of the source code:

def start(server):

res = ''.join(random.choices(string.ascii_letters + string.digits, k=5))

key = str(res)

hex_encoded = setup(server, key)

Here’s where the encryption key is generated. It takes all the letters (both lowercase and uppercase) and numbers, then forms a string of 5 characters. This key is then passed on to the setup function:

def setup(server, key):

flag = 'THM{thisisafakeflag}'

xored = ""

for i in range(0,len(flag)):

xored += chr(ord(flag[i]) ^ ord(key[i%len(key)]))

hex_encoded = xored.encode().hex()

return hex_encoded

This is the bread and butter we need to start our decryption journey. An XOR (eXclusive OR) function is used to get a new string that is then hex encoded. This hex-encoded string is what we see on our screen from the netcat call.

Let’s us first play around with the XOR operator in python to see how it works.

print(5 ^ 4) # 1

print(5 ^ 5) # 0

print(5 ^ 6) # 3

print(5 ^ 8) # 13

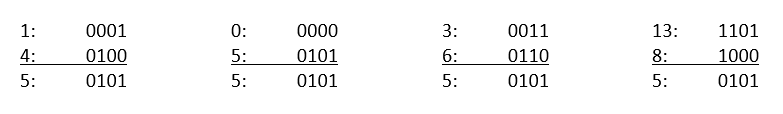

If you’re scratching your head wondering what it does, the output might seem like random gibberish, but there’s a method to the madness. XOR is a bitwise operator, meaning it works on the binary level of the given inputs. If both bits on the same location on a input are both 0 or both 1, the output bit is a 0. If one bit is a 1 and the other one a 0, the output bit is a 1. In the examples above, these are the outputs on binary-level:

The nice thing about XOR operations is that they are reversable. I we take the output of the first XOR examples and we do another XOR operation on the second input of the first XOR operation, we get the other input back!

This means we can use the same key to decrypt a message that was used to encrypt it in the first place. This is why using the same key for both encryption and decryption is considered unsafe. In SSL (HTTPS), we use a public key and a private key for this reason. The public key encrypts a message and is freely sent over the internet, while the private key, which never goes over the internet, pairs with the public key to decrypt the message.

Let’s start by encoding a numerical value using a numerical key. To encrypt every digit separately, I made both the message and the key strings so we can loop through the digits. For now, I store the output in a list for readability and usability in the code:

message = "1234"

key = "6789"

xored = []

for i in range(0,len(message)):

xored.append(int(message[i]) ^ int(key[i]))

print(xored) # [7, 5, 11, 13]

old_message = ''

for i in range(0,len(xored)):

old_message += str(xored[i] ^ int(key[i]))

print(old_message) # 1234

However, if our message is longer than the key, we run into a problem. The code will break after the 4th character because there is no 5th element in the key. We can fix this by using the modulo operator % in Python. Modulo divides a number by another number and returns the remainder (so 8 % 3 = 2 and 12 % 6 = 0). By using modulo on the index of the message by the length of the key, we can loop through the key for each character in the message. This was also done in the source code.

message = "123456789"

key = "6789"

xored = []

for i in range(0,len(message)):

xored.append(int(message[i]) ^ int(key[i%len(key)]))

print(xored) # [7, 5, 11, 13, 3, 1, 15, 1, 15]

old_message = ''

for i in range(0,len(xored)):

old_message += str(xored[i] ^ int(key[i%len(key)]))

print(old_message) # 123456789

Letters are also just binary numbers that our computer decodes into the letters we see on the screen using the ASCII converstion table So for letters, the XOR operator works the same way, just with larger binary numbers. To use the XOR operator in Python, we first have to convert the letters to their Unicode characters, which are integers, using the ord() function in Python. Now let’s try to to encrypt a message in text using the ord() funcion. To decrypt the message again, we use the oposite of the ord() function, namely the chr() function:

message = "hello world"

key = "key"

xored = []

for i in range(0,len(message)):

xored.append((ord(message[i])) ^ (ord(key[i%len(key)])))

print(xored) # [3, 0, 21, 7, 10, 89, 28, 10, 11, 7, 1]

old_message = ''

for i in range(0,len(xored)):

old_message += chr(xored[i] ^ ord(key[i%len(key)]))

print(old_message) # hello world

Now let’s get rid of the list. Storing numbers as strings isn’t ideal because we can’t differentiate if 123 is 12 en 3 or 1 and 23. So we translate each number to a character and store that instead. However, the characters are not readable in the output, so we encode it in hexadecimal before printing it to the console.

message = "hello world"

key = "key"

xored = ""

for i in range(0,len(message)):

xored += chr((ord(message[i])) ^ (ord(key[i%len(key)])))

print(xored.encode().hex()) # 030015070a591c0a0b0701

old_message = ''

for i in range(0,len(xored)):

old_message += chr(ord(xored[i]) ^ ord(key[i%len(key)]))

print(old_message) # hello world

And now we basically have the encryption algorithm that the source code uses. With this knowledge, we can decrypt a message if we know the key that was used. Now, we can work on guessing the key.

The Bruteforce method

In our previous exploration, we knew the key and the original message. If we have the encrypted message, we need the key or the original message to get the other one. This is basic math that you can easily solve if you have one variable. If you have two, well… advanced math! Or… dumb guessing. I chose the latter first, which isn’t the best approach. But if you’re stuck, you can try this brute-forcing technique and maybe get lucky. If you want to better approach to this machine, you can skip this section.

If we netcat to the machine again, we see the encoded text changes each time we connect. This is because the key is randomly generated each time you connect, and therefore the output changes as well:

┌─[user@parrot]─[~]

└──╼ $netcat 10.10.56.68 1337

This XOR encoded text has flag 1: 03297b303866005a253c1219420a3c235555202b160f4478293b2d4f231d25154f7b3d2519793935

What is the encryption key?

┌─[✗]─[user@parrot]─[~]

└──╼ $netcat 10.10.56.68 1337

This XOR encoded text has flag 1: 00261a2b1e650f3b3e1a111623111a205a343b0d150025630f38222e383b261a2e601b2616182213

What is the encryption key?

We can take the encoded message and start generating random keys, trying them all to see if one of them fits. We know from the source code that the length of the key is 5 characters long (the k=5 parameter). We filter the messages that start with THM, as flags usually start with this and it was also given as an example in the source code. To ensure we only try a key once, I constructed a list of all tried keys.

import random

import string

xor_output = "35192a344750300b21432429130e431565042454203f157c560d1d1e276213251e7f421329283d4a"

key = "aaaaa"

used_keys = [key]

decrypted_msg = ''

# Don't forget to decode the output first!

encrypted_msg = xor_output.encode().hex()

def gen_key():

new_key = ''.join(random.choices(string.ascii_letters + string.digits, k=5))

used_keys.append(new_key)

return new_key

while True:

for i in range(0,len(encrypted_msg)):

decrypted_msg += chr(ord(encrypted_msg[i]) ^ ord(key[i%len(key)]))

if decrypted_msg[0:3] == "THM":

print(key, decrypted_msg)

key = gen_key()

decrypted_msg = ''

I let this script run for a few minutes, but it didn’t return any possible keys. I wanted to know how many possibilities I had to test to try all possible keys. We have 26 lowercase and 26 uppercase letters plus 10 digits for each position in the key. This means we have 62 options per digit. Because we have 5 digits in total, we have 625 options in total to check! That’s 916,132,832 options in total! If we perform 1,000 checks a second, this will take over 10 full days to complete. But with this code, it’s even worse. We generate a random key every cycle. As our list gets more filled up, it takes longer to check if we’ve already used a key, and the probability of generating a duplicate key increases. This is not the way to go. So, I started generating unique keys with a new function:

import string

xor_output = "35192a344750300b21432429130e431565042454203f157c560d1d1e276213251e7f421329283d4a"

key = "aaaaa"

decrypted_msg = ''

# create a list with all possible characters

options = []

for letter in list(string.ascii_letters):

options.append(letter)

for number in list(string.digits):

options.append(number)

# options = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', 'g', 'h', 'i', 'j', 'k', 'l', 'm', 'n', 'o', 'p', 'q', 'r', 's', 't', 'u', 'v', 'w', 'x', 'y', 'z', 'A', 'B', 'C', 'D', 'E', 'F', 'G', 'H', 'I', 'J', 'K', 'L', 'M', 'N', 'O', 'P', 'Q', 'R', 'S', 'T', 'U', 'V', 'W', 'X', 'Y', 'Z', '0', '1', '2', '3', '4', '5', '6', '7', '8', '9']

# Don't forget to decode the output first!

encrypted_msg = xor_output.encode().hex()

def gen_key():

changed = False

new_key = ''

for i in range(0, len(key)):

if key[i] == options[-1] and not changed:

new_key += options[0]

continue

elif changed:

new_key += key[i]

continue

new_key += options[options.index(key[i])+1]

changed = True

return new_key

while True:

for i in range(0,len(encrypted_msg)):

decrypted_msg += chr(ord(encrypted_msg[i]) ^ ord(key[i%len(key)]))

if decrypted_msg[0:3] == "THM":

print(key, decrypted_msg)

key = gen_key()

print(f"trying key: {key}")

decrypted_msg = ''

To generate unique keys efficiently, I first made a list of all possible options for a character to be. The key_gen() function increments the first character of the key by one on the options list. When the first character becomes a 9, it has depleted the options list. When this happens, this character becomes the letter a again and increments the second character by one. I added a changed boolean variable to prevent every 9 in the key from becoming an a prematurely (we want to check b9aaa after a9aaa. Without the boolean, after a9aaa, the key would become baaaa, which we already checked.)

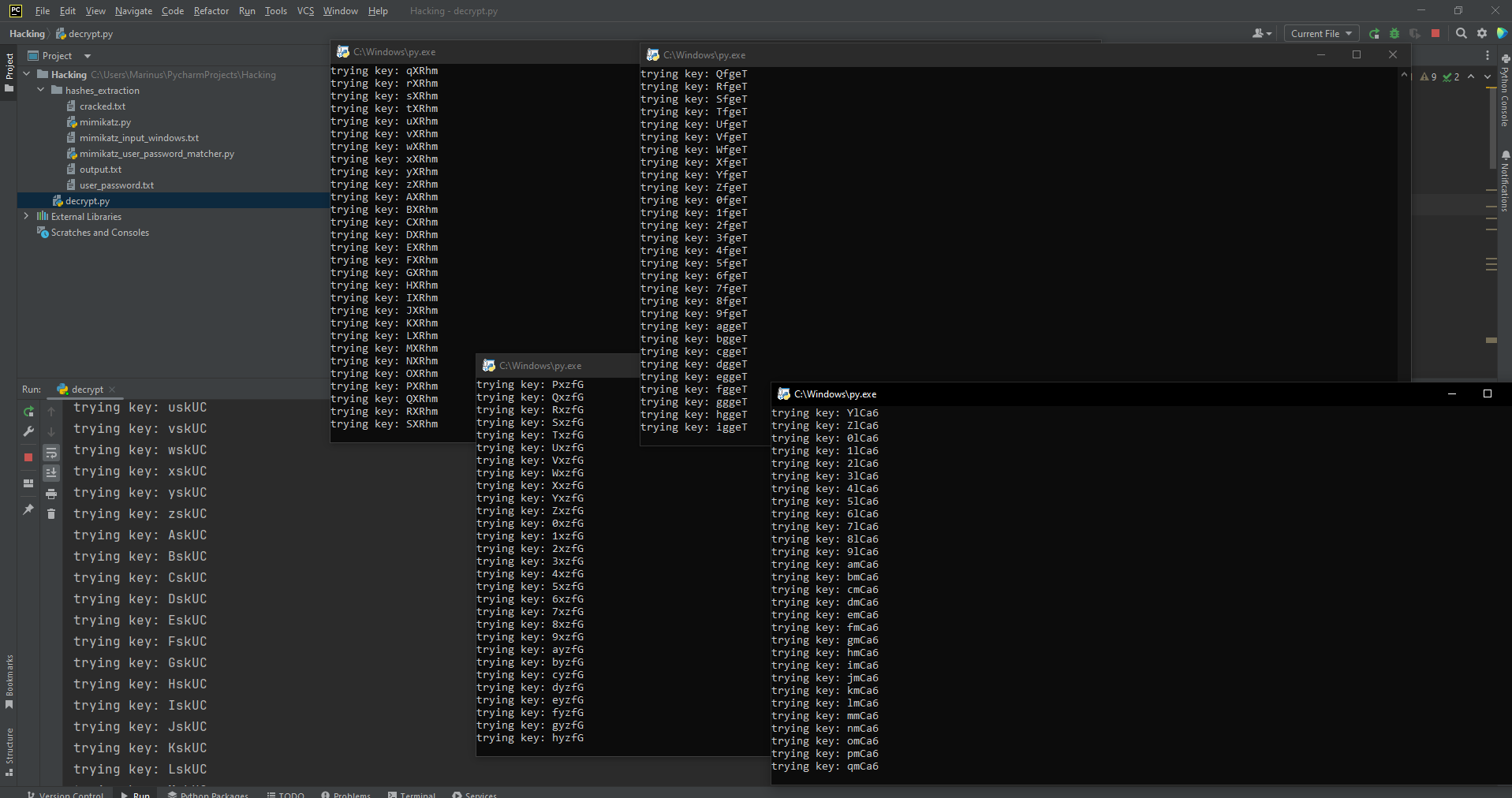

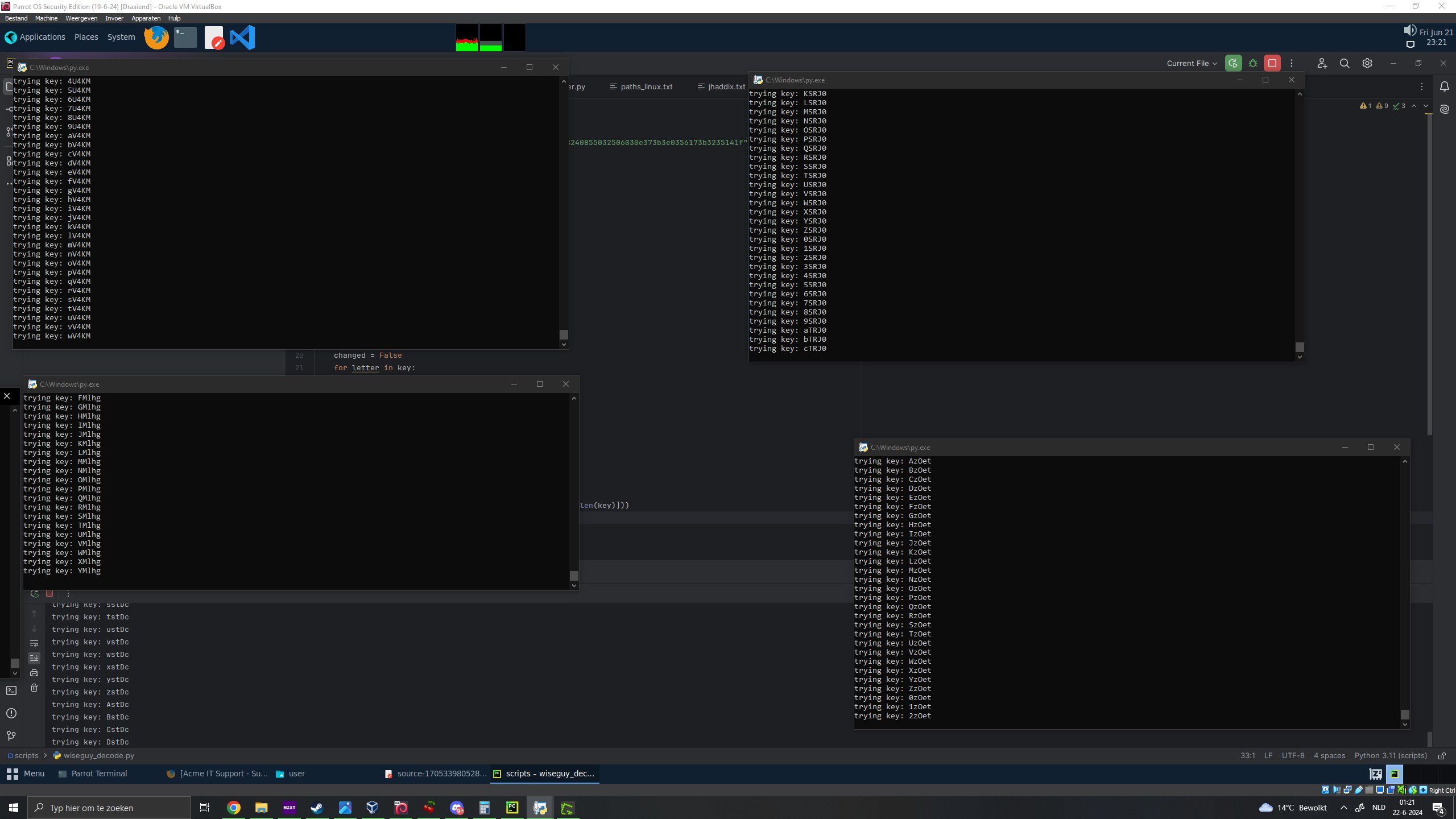

While this code is much better, it still requires a lot of brute-forcing. To speed up the process, I ran multiple Python scripts simultaneously, each with different starting points on the last digit (which takes the longest to change with this script.)

With patience and by clicking that add 1 hour button on the room to prevent the machine from terminating, you can definitely find the key you need eventually. But we can do soooo much better if we think a little bit harder. So here’s my challenge for you:

Can we eliminate an entire family of keys that we know won’t work based on a common characteristic??

The clever method

When I made the approach described above, it was already late at night and I just wanted to get the flag. I eventually went to bed and came back to it in the morning with a clear head. We were already filtering the decrypted output for a match of the letters THM. We can make use of this in a more efficient way.

Imaging if the key ‘Qaaaa’ results in an output of TPOadkK....., We see that we have the first letter of the decrypted message right. Since each character of the flag is encrypted once by a single character of the key (the first letter by the first character of the key), we already know the first character of the key must be Q! This allows us to eliminate all other 61 options for the first character. We also know the value of the second (H) and third character (M) of the flag. But think about it, what comes after THM in a flag? the { symbol! By finding a match for every single character in order, we already have 4 out of 5 characters of the key! If we know the first 4 characters, we only have to check 62 more options to find the correct flag.

import string

xor_output = "35192a344750300b21432429130e431565042454203f157c560d1d1e276213251e7f421329283d4a"

key = ''

key_length = 5

target_letters = ["T", "H", "M", "{"]

# decode the xor_output back

decode_xored = bytes.fromhex(xor_output).decode()

# create a list with all possible characters

options = []

for letter in list(string.ascii_letters):

options.append(letter)

for number in list(string.digits):

options.append(number)

# search for matching key characters that lead to the right character on the right position in the decoded string

def key_gen(encrypted_char, target):

for i in range(len(options)):

found_char = chr(ord(encrypted_char) ^ ord(options[i]))

if found_char == target:

return options[i]

# We decrypt one letter at the time and find a matching key character for it. We construct the key this way letter for

# letter, instead of brute forcing all the possible keys.

for i in range(key_length-1):

key += key_gen(decode_xored[i], target_letters[i])

# Now we know the key and can use it to decrypt the xored encrypted message

for char in options:

full_key = key+char

decrypted_msg = ''

for i in range(0,len(decode_xored)):

decrypted_msg += chr(ord(decode_xored[i]) ^ ord(full_key[i%len(full_key)]))

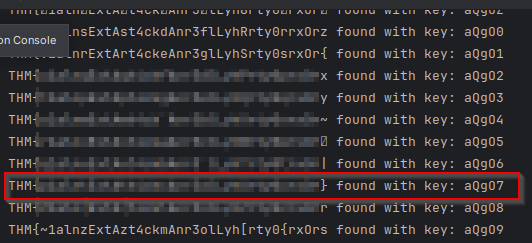

print(f"{decrypted_msg} found with key: {full_key}")

By focusing on these patterns, the flag becomes more readable, and we find the right flag along with the corresponding key:

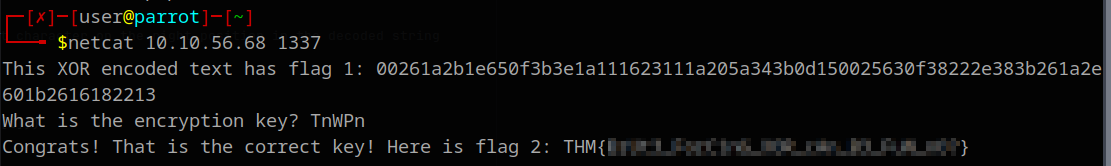

Once we have the key, we can use it to get the second flag as well. (I had to use it with a different key on the machine shown above, but the method is the same.)

But hold up there! We are not done yet

While this method works fine, I like to keep this script as a tool for later and it’s still not optimized. Can you make this script output the correct key and flag in one go? I know you can do it!

When searching for the flag, we can also focus on the last character being a }. Now we have 5 characters in total that we want to force into our decrypted message, eliminating one of the variables we didn’t know before, namely the original message. We might not know it in its entirety, but we know just enough to find the key in the most optimal way. We just have to tweak our code a bit to check for the } at the end of the decrypted message, and if it shows up, we print the key that fits with the flag that is 100% correct every time within a second!

import string

xor_output = "35192a344750300b21432429130e431565042454203f157c560d1d1e276213251e7f421329283d4a"

key = ''

key_length = 5

target_letters = ["T", "H", "M", "{", "}"] # we add the } character to the list we want to check for in the output

decrypted_msg = ''

# decode the xor_output back

decode_xored = bytes.fromhex(xor_output).decode()

# create a list with all possible characters

options = []

for letter in list(string.ascii_letters):

options.append(letter)

for number in list(string.digits):

options.append(number)

# search for matching key characters that lead to the right character on the right position in the decoded string

def key_gen(encrypted_char, target):

for i in range(len(options)):

found_char = chr(ord(encrypted_char) ^ ord(options[i]))

if found_char == target:

return options[i]

# We decrypt one letter at the time and find a matching key character for it. We construct the key this way letter for

# letter, instead of brute forcing all the possible keys.

for i in range(key_length):

if i < key_length-1:

key += key_gen(decode_xored[i], target_letters[i])

else:

key += key_gen(decode_xored[-1], target_letters[i]) # this part checks the last character of the decrypted string to find the final character of the key

# Now we know the key and can use it to decrypt the xored encrypted message

for i in range(0,len(decode_xored)):

decrypted_msg += chr(ord(decode_xored[i]) ^ ord(key[i%len(key)]))

# Print the result in the console

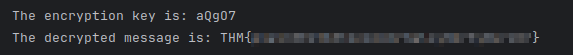

print(f"The encryption key is: {key}")

print(f"The decrypted message is: {decrypted_msg}")

And here is our only result in the console:

This script can be easily altered for future encounters with the XOR encryption method. Simply adjust the variables at the top of the script for key_length and target_letters if they differ in that situation. It’s always a good idea to craft your scripts to solve a general problem and not just serve a singular purpose, so you can add them to your toolbox. We can optimize the script further to run through a console command, but that’s a challenge I’ll leave you to figure out on your own.

For now, thank you for reading, happy hacking, and until next time! And remember, even if you feel like a n00b, every bit of progress makes you a wiser n00b.